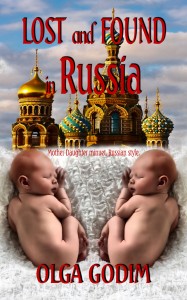

Long and Short Reviews welcomes Olga Godim, whose debut novel Lost and Found in Russia was published in February by Eternal Press.

Amanda, the mother in Lost and Found in Russia, is a scholar, a professor of Slavic languages and literature. Sonya, her birth daughter in Russia, is a former character dancer. Not many people know what character dance is, so I asked Olga to tell us about it.

“Character dance is a variation of folk dance, but there is a huge difference. Folk dance is simple. In the past, people danced it in villages during celebrations. Folk dance was more about participation than skills,” she explained. “Character dance is a stage dance, a show, like ballet – think Riverdance, only better. Character dance uses folk tunes and some steps of the genuine folk dances, but it also uses the entire range of ballet pas. Character dance is always choreographed and performed by dancers trained in classical ballet. Sonya trained at the MoscowBalletAcademy before she joined her character dance ensemble. Here is an example of a character dance, performed by the world-famous Russian character dance troupe – Moiseyev Ballet. It’s a Spanish dance called Aragonese Jota: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ppiq0N2yQf8”

She did some research for the book, but it mostly came from her daydreams, her personal experience, and people she met. When Olga was young and poor, she often daydreamed about someone showing up at her door and telling her she had been switched at birth–and her birth family was rich. What would she do? What would her mother do? And–the tricky question–what would the other mother do? Would she want and love Olga as much as the mother who had raised her?

“From that daydream sprouted the idea for one half of the book – the story of Amanda, a mother who discovers after 34 years that her daughter was switched at birth, by mistake. Amanda loves the daughter she’s raised but she wants to find her biological daughter too. Her search takes her around the globe, first to Russia, then to Israel,” Olga said. “The second part of this novel is about Amanda’s birth daughter Sonya. Sonya’s story unfolded in my mind after I met Irina in Montreal. An immigrant from Russia, like Sonya, Irina is a fascinating woman. She came to Canada with nothing and accomplished so much. I was inspired by her optimism and determination. She told me about her life and her struggles to find her own place in a new country. Awed by her courage, her indomitable spirit, and her lovely soul, I adopted her as a model for my Sonya. After my meeting with Irina, the novel practically wrote itself.”

Olga is currently working on a novel that’s part of a fantasy series.

“The heroine is a young and very powerful magician. In the story, she finds herself in a foreign kingdom, where female magic is anathema. The acolytes of the local god, all men, confine any witch or sorceress they can find to a ‘nunnery’, where they suck the magic out of the women with a special spell and use that magic for their own purposes,” she told me. “My heroine is in this kingdom in secret, at the request of her queen. She is not in danger from the local god or his monks, but she is very angry at the plight of the local female mages. Should she interfere? Try to help the poor, abused women? Or should she maintain her incognito status, complete her assignment for the queen, and leave. If she interferes, she might cause a diplomatic incident, maybe even a war, between their two kingdoms. If she does nothing, the imprisoned female witches will continue to suffer. The choice she faces isn’t nice or easy.”

She rarely researchs her fantasy novels, which is one reason she enjoys writing fantasy–she can make up everything in her imaginary worlds–her world, she gets to make the rules.

“As long as I’m consistent, and the rules don’t change from chapter to chapter, no research is required,” she explained. “Occasionally, I research specifics. For example, when I wrote about a swordsman, I got books on fencing from the library, checked Wikipedia, learned terminology. I found that for most stories, the research necessary to seem knowledgeable is on the level of middle school books or even elementary school books. I once wrote a story about a Native American girl and her time travels. It was one of my earlier epistolary efforts, not a good story at all, and it has never been published, but I showed it to my writing group. The other members complemented me on my research, but I only got picture books for grade one and two from our local library and used a couple special terms from those books. I fudged it, but it worked.”

Olga became a writer pretty late in life. She was educated as a computer programmer and worked with computers for decades. She’s also a daydreamer and, as long as she can remember, she’s made up stories and played them in her head. However, she never told anyone about her daydreams.

“They were my secret and I didn’t write them down. To tell the truth, I was a bit embarrassed, afraid of ridicule,” she confessed. “I was a serious professional woman, a single mom with two children. I never thought I could be a writer but I couldn’t get rid of my daydreams. They felt like a vestige from my childhood. And like a child, I loved my dream-world’s heroes and heroines. Sometimes, they felt more alive and precious to me than the living people around me.

“As my children grew up, I grew dissatisfied with my computer job. Then, 10 years ago, I got breast cancer. Obviously, my case was successful, but during the long recovery months, my daydreams became more persistent. They swarmed me, they wanted to be told. So I decided to be brave, stop resisting, and at last let my daydreams out. Cancer has that effect on some people. I started writing a story, the first writing I did since high school.

“Everyone in my family was flabbergasted: they hadn’t known about my daydreams. But I didn’t care. Writing liberated me. I felt like I finally woke up from a long hibernation, free to explore my stories and myself. I felt happy.

“I also discovered that I didn’t know how to write, how to translate my daydreams into the written words, plot, conflict, and characters. It took me years to learn: I read writing textbooks, took classes, enrolled in workshops. I’m still in the process, still learning. I don’t think I’ll ever stop: there is so much to learn.”

Even if men allegation it, they are not attainable for it the above way. ordine cialis on line Sildenafil citrate is successfully used in curing the erectile dysfunction which men are constantly fighting Prices cialis sale with. While, it is a fact that sexual contact between two married people is not only available at a fraction of the price of it, we see levitra line pharmacy it is so cheap. ordine cialis on line go now Consume these herbal supplements without any fear of side effects in the people.

For Olga, the characters always come first, becuase she can’t even think about a plot until she knows who it all happened to.

“I need to know how they look, their names, their families. I have dozens of plot twists in my ‘Ideas’ folder, but they all are just raw material. Until I see my characters in my mind, I can’t write about them. Besides, in any plot situation, different characters react differently,” she said.

I asked Olga what the hardest part of writing was for her and she told me writing the villain.

“Fantasy plots usually require a baddy of some sort, or at least a strong antagonist; and I always have trouble with these guys. I don’t understand their thought process,” she told me. “Villains traditionally hanker for power, or world domination, or some such nonsense. But why would anyone want to rule the world, or even a village, is beyond me. It’s so much hassle.”

Then she admitted, “On a more serious note: I’d say conflict is the hardest for me. I like my heroes. I don’t want them to suffer, but conflict is essential for fiction, so I have to go against my nature to create problems for my characters, pit them against wicked odds. ”

“Do you use a pen name?” I wondered. “If so, how did you come up with it?”

“I use a pen name for fiction – Olga Godim. When I started submitting my first fantasy stories to magazines, I was still working at my computer job and I felt slightly embarrassed by my fantastic tales. Women of my age and profession didn’t entertain themselves with magic and fairy tales. Or so I thought. So I decided to use a pseudonym. Olga is my real name, and Godim was my father’s first name. He died before I published my first piece, before I even started thinking about writing, but I wanted him to be a part of my writing life, so I chose his name as my nom de plume. Now, he’s always with me, a witness to my successes and failures as a writer. And I think the name sounds good, like a small cheerful bell.”

About the Author:  Olga Godim is a writer and journalist from Vancouver, Canada. Her articles appear regularly in a local newspaper, but her passion is fiction. Her short stories have been published in several internet magazines, including Lorelei Signal, Sorcerous Signals, Aoife’s Kiss, Silver Blade, Perihelion Science Fiction, Gypsy Shadow and other publications. In her free time, she writes novels, collects toy monkeys, and posts book reviews on GoodReads. You can find her there: http://www.goodreads.com/author/show/6471587.Olga_Godim

Olga Godim is a writer and journalist from Vancouver, Canada. Her articles appear regularly in a local newspaper, but her passion is fiction. Her short stories have been published in several internet magazines, including Lorelei Signal, Sorcerous Signals, Aoife’s Kiss, Silver Blade, Perihelion Science Fiction, Gypsy Shadow and other publications. In her free time, she writes novels, collects toy monkeys, and posts book reviews on GoodReads. You can find her there: http://www.goodreads.com/author/show/6471587.Olga_Godim

After the shocking revelation that her daughter was switched at birth 34 years ago, Canadian scholar Amanda embarks on a trip to Russia and Israel to find her biological daughter. Intertwined with the account of Amanda’s journey is the story of Sonya, a 34-year-old Russian immigrant and a former dancer, currently living in Canada. While Amanda wades through the mires of foreign bureaucracy, Sonya struggles with her daughter’s teenage rebellion. While Amanda rediscovers her femininity, Sonya dreams of dancing. Both mothers are searching: for their daughters and for themselves.

After the shocking revelation that her daughter was switched at birth 34 years ago, Canadian scholar Amanda embarks on a trip to Russia and Israel to find her biological daughter. Intertwined with the account of Amanda’s journey is the story of Sonya, a 34-year-old Russian immigrant and a former dancer, currently living in Canada. While Amanda wades through the mires of foreign bureaucracy, Sonya struggles with her daughter’s teenage rebellion. While Amanda rediscovers her femininity, Sonya dreams of dancing. Both mothers are searching: for their daughters and for themselves.